A staggeringly large proportion — 94% — of global executives are dissatisfied with their organization’s innovation performance, according to a recent McKinsey global survey of large cap firms. And only 31% of senior managers were “reasonably confident” they could reach their organic growth targets (which typically means growth driven by innovation). Why the tremendous lack of confidence? asked Wharton marketing professor George Day, in a keynote delivered at the Mack Institute 2019 Fall conference.

Part of the uncertainty around innovation stems from the difficulty of measuring it. While metrics abound, none are universally accepted. They range from basic quantitative ones — such as tracking the number of patents issued — to much more qualitative, like assessing a firm’s “culture of innovation.” Moreover, the challenge of identifying the best measures is becoming more difficult in a world of swiftly changing business models, increasing digitization, and the pressure to show quarterly financial results.

The conference attracted executives from health care, financial services, information technology, telecommunications, publishing, and other industries, along with academic experts. Attendees addressed challenges and opportunities as they discussed how to design the best innovation metrics for different firms and projects, and shared successful (and not-so-successful) practices.

Mack Institute executive director Saikat Chaudhuri commented on the benefit of looking across firms and sectors for solutions: “At a macro level, the challenges of managing innovation are really similar when it comes to thinking about how to get larger organizations to become more nimble, adapt, and be agile. These are themes we all care about.”

He set the stage with a basic question: Why measure innovation? The answer is that if a company wants to put money into developing new products, services, or business models, its executives need to assess the effectiveness of its current approach to innovation. Moreover, such metrics yield valuable information that can be used to incentivize managers and to hold them accountable. Above all, said Chaudhuri, having reliable innovation metrics helps us set strategic direction, including determining how to evaluate new ideas and allocate resources.

But measuring innovation can be anything but straightforward, he said. For instance, many companies rely on easily-obtained financial metrics such as revenue growth or percentage of sales from new products, but it’s difficult to tie those exclusively to specific innovations or innovative processes. “We often measure what’s available [to measure,] as opposed to what’s needed,” he observed. Chaudhuri noted that the Mack Institute is actively engaged in developing new, more effective approaches to measuring innovation, which will be published in a future report.

Co-director Harbir Singh emphasized the key role of innovation in today’s business environment. “If you look at the top ten companies in market cap today, six of them did not exist in the mid-eighties. Many big ones have fallen out of the [ranking] and been replaced by firms that have tremendous income coming from essentially intellectual property. So the stakes are extraordinarily high.”

Anne Marie Knott on How to Measure Innovation

As a project engineer at Hughes Aircraft in the 1990s, Anne Marie Knott was dismayed when the firm was acquired by General Motors and the new owners started reorganizing Hughes’ R&D functions. “I said, ‘this is terrible, it’s going to permanently degrade our R&D capability,” Knott recalls. But she couldn’t convince anyone else. Why? Hughes had no reliable, agreed-upon way to measure its R&D success, hence no way to demonstrate it was deteriorating.

Fast forward to today, and businesses are still seeking the holy grail of meaningful innovation metrics. Knott, now a business professor and corporate advisor, presented the attendees with new and existing measures of R&D productivity.

Knott observed that there are dozens of known ways to measure innovation. However, “there aren’t uniform standards; there’s concern that you can game the measures so one group gets more resources than another; and perhaps most importantly, they’re not meaningful to investors.”

A convenient measure to which many firms turn is the number of patents issued, Knott said. However, she pointed out, only 50% of firms that engage in R&D file any patents, and of those that do, only 40% file in a given year. So the usefulness of that metric is limited.

Knott led the participants through several commonly used innovation measures. One is the Vitality Index, which tallies the percentage of revenues from new products launched in the past three years. But the definition of “new” can vary, and this approach also fails to measure process innovation and incremental innovation. Another one is the McKinsey R&D Productivity Measure, which projects the expected value of a company’s R&D initiatives, and tracks progress to date divided by the amount of R&D spending. “What’s the big problem with that one?” asked Knott. “It’s a forecast, [not a measure], and R&D forecasts are notoriously unreliable.”

Knott also discussed the Holt Innovation Premium method, the basis for Forbes’ well-known “The World’s Most Innovative Companies.” A firm’s innovation is measured by its market cap minus the net present value of forecasted cash flows. She noted that a major caveat is stated by the authors themselves: there’s no correlation between their method and actual returns to investors.

The “RQ” or Research Quotient measurement is Knott’s contribution to the field, based in part upon a Nobel Prize-winning theory by economist Paul Romer. “It’s intended to be a company equivalent of individual IQ… Just as smart individuals solve more problems per minute, smart firms solve more technical problems per dollar of R&D.” Knott stated that the RQ approach possesses the most important properties for an innovation measure: it’s reliable, universal, and uniform. She said that based on nearly 50 years of research, increasing RQ increases optimal R&D investment, market value, and overall firm growth.

Outlining a larger economic vision, Knott described a scenario in which investors would use the RQ method to value stocks, which would shift their investment toward high-RQ companies. That would spur companies to try to boost their RQ, generating higher returns. Ultimately, said Knott, we would see increases in business’s RQ — and a corresponding boost in America’s GDP.

Sharing Perspectives from Industry

Panelists from the pharmaceutical industry and transportation sector discussed their efforts to innovate, and measure innovation, against the backdrop of digital and other massive changes in their sectors.

Yvonne Phan, a global senior manager at AstraZeneca, described the firm’s recently-launched digital platform designed to reach health care practitioners and insurance companies. The platform sits on the medical affairs side of the business, however, which Phan said subjected it to certain FDA regulations. “There’s a very small sandbox we’re allowed to play in, and we’ll get fined it we go beyond it.”

On the consumer side of AstraZeneca’s business is James Smith, a director of marketing. His team, too, is looking toward digital. He explained that a traditional TV campaign can reach millions of people, but they may not be potential users of a particular medication. Digital changes the game. “Pharma’s starting to get into that space where we can use information about your digital footprint… about your medical history, and we can start to target patients more effectively.”

Andre Costa, the chief information officer of CCR S.A. in Brazil, a major infrastructure services company in Latin America handling the operation of motorways, subways, and airports, discussed his use of open innovation: collaborating with a hub of players to solve business challenges. He noted that one recent success involved redistributing the number of passengers in subway cars in order to improve passenger experience and reduce electricity costs. This was a major win, he explained, because electricity constitutes 70% of the subways’ operating expenses.

Singh noted that all three panelists were tackling new business models, such as the introduction of digital platforms and open innovation. It’s difficult to measure innovation in these cases, he said, because the process is still evolving. He asked the panelists about their baselines and how they determined what to measure.

Costa noted that it’s difficult to set up a baseline in the infrastructure services industry because airports and roads, for instance, are dramatically different projects. In addition, “in infrastructure, you build something to last 100 years,” which makes some measurement timeframes problematic. He said CCR builds business cases using a metric known as total cost of ownership (TCO), and also assesses how innovation is improving customers’ everyday lives.

Phan noted that on the medical affairs side she’s prohibited from tying dollar values to innovation activities. “So it’s tricky for us to find very directed metrics to ensure we’re putting money into where it’s worth it.” For the new website, she does track site visits and return visits, and resources downloaded or emailed to others. Hence she is able to calculate something similar to CLV, or customer lifetime value. She has also purchased data from the site metrics of competitors in an effort to set baselines.

Smith commented that for his commercial digital solution, his team brought in patients and physicians to help co-create the site. He reflected, “Having customer input, and on an ongoing basis to refine it, has made [the site] better and helped us understand where we should invest the money.”

Singh acknowledged the complexity of the innovation measurement problem, wrapping up by saying, “This is a moving target; we’re not going to have closure.” Yet we can continue to apply analytics, he said, to come up with ever-more effective measurement models down the road.

Getting Your People to Think Innovatively

Introducing the Designing Incentives panel discussion, Chaudhuri said that besides measuring innovation in terms of “what we have achieved,” organizations must “promote the right behavior in order to further innovation, both radical and incremental.”

Venkateswara Duggirala, a digital innovation director for Tata Consultancy Services, talked about how businesses need to make sure employees’ incentives to innovate are aligned with the firm’s overall metrics. For example, someone’s KPIs might focus on generating thought leadership and ideation, yet the metric the company really values is revenue from digital sales. A situation like that, he said, causes tension: it’s a zero-sum game. Ryan Sjostrom, a senior director of marketing at Novo Nordisk, agreed that for example, “if my incentives are based solely on stock price or corporate value but I’m looking to radically innovate, this conflict can stress leadership tolerance, acceptance, or initiation of significant change.”

Duggirala added that incentives to innovate need to be diffused through every level of the organization, so that “fresh eyes and fresh minds” — not to mention subject matter expertise — can be applied to achieve innovation.

A managing director at JPMorgan Chase, Kunal Vaed spoke about metrics which he said help attract and retain talent and promote an innovative mindset. One is JPMorgan Chase’s App Store rating, which Vaed stated is among the highest of all banks. Another is the firm’s active mobile users, where JP Morgan Chase leads the industry with 37.3 million as of Q4’19. These two indicators suggest that the digital side of the company is “satisfying and delighting customers.”

Another metric Vaed focuses on is the extent to which senior management spotlights technology in public statements. Such statements attract talent by expressing what the company values, he said. He noted that JPMorgan Chase’s CEO Jamie Dimon’s 2008 shareholder letter only mentioned technology once, but the most recent letter mentioned it 21 times. “So as a bank, we have recognized, and the leadership has bought into the idea, that technology is the beginning of innovation.”

Financial compensation has long been an incentive for employees, of course, both to stay with the firm and to engage in the innovative behaviors the firm seeks. But the panel agreed that younger workers in particular are incentivized by more than money. Employees care about company culture, workplace environment, and the firm’s social impact. Duggirala and Sjostrom named employee happiness and talent retention as metrics that should be included in any incentive system.

“Clearly, incentives matter,” Chaudhuri summed up. “We know that they drive behavior. They also matter because of the misalignment problem we’ve been talking about: They can actually steer you away from innovation and other growth goals… So you want to make sure to get that right.”

Workshop: Developing Metrics for Innovation

In the workshop, participants were tasked with assessing the state of measuring innovation in their firms or divisions.

Chaudhuri offered a framework for thinking about innovation metrics, dividing 23 quantifiable metrics into three categories. First were inputs, such as R&D spending, the idea pipeline, and human resources devoted to innovation. Next were process effectiveness measures, such as patents commercialized, and average time to market for new products. The third category was performance outcomes, or outputs, such as ROI on investment in innovation, percent of sales from new products in a given number of years, and customer satisfaction.

Examples of Quantifiable Metrics

Inputs

- R&D spending (percent of sales)

- Human resources devoted to innovation

- Pipeline of ideas/concepts

- Number of R&D projects in active development

- Percent of ideas/concepts from outside the firm

- Ratio of ideas from inside/outside

Process Effectiveness

- Development activities

- Percent hitting gates on time

- Percent meeting quality

- Guidelines

- Patenting activity

- Number filed

- Number commercialized

- Percent covered by patents

- Budget vs. actual

- Time

- Cost/investment

- Average time to market

- Number of new products launched

- Percent of projects that are major improvements

Performance Outcomes

- Percent of sales from new products in past N years

- Success ratio (percentage of meeting financial goals)

- Revenue growth

- Return on investment in innovation (ROIC)

- Percent of profits from new customers (or occasions)

- Percent of profits from new categories

- Average time to break-even/cash

- Customer satisfaction

- Profit growth due to new products/services

- Percent of profits from new products in a given period

- NPV of portfolio

- Potential of portfolio to meet growth targets

Chaudhuri noted that output measurements, while popular among companies because of their relative ease of tracking, may not always be the most useful or relevant metrics. Process effectiveness measures on the other hand, while trickier to quantify, often are the ones that truly help a firm move innovation forward.

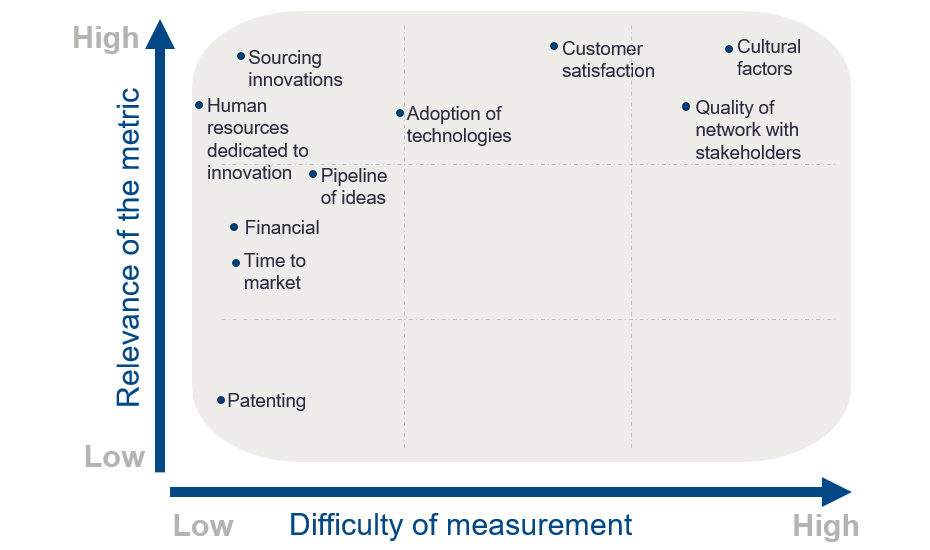

Relevance vs. Difficulty of Metrics

Among the workshop participants, common themes emerged. One was the conundrum of classifying and measuring early-stage versus late-stage innovations. An investment management specialist involved with early-stage ideation and proof-of-concept talked about the difficulty of demonstrating how new ideas were aligned with company strategy or value to investors. One basic metric she used was the number of projects in the pipeline. She noted that a fellow participant on the other hand, who worked for a pharmaceutical company, was involved with the more mature go-to-market phase. He reported success with using a time-to-market measurement.

An executive of a major publishing house discussed classifying innovations using McKinsey’s Three Horizons model of innovation. (H1 innovations are incremental whereas H3 ones are more radical.) He noted that while this organizing principle is useful in some ways, it can create unwelcome competition for resources among managers of the innovation groups. Singh agreed and noted that it’s also important to apply different metrics to the different stages so you’re not comparing apples to oranges.

The issue of measurement timeframe was raised by an information technology executive. “Clearly, financial metrics are widely used for revenue growth and for market impact. But the question is, over what timeframe makes sense?” Participants discussed the quarter-to-quarter thinking that prompts some CEOs to expect fast — and not always realistic — results from innovation. Chaudhuri speculated that with the current emphasis for companies on longer-term planning, perhaps this will become less of an issue.

When talking about innovation measurement, we should also include measuring failures, said a transportation industry expert. “If you embrace them and learn well, you will be better the next time.” Singh agreed it was important for companies to measure their failure rate. On the one hand, “failure is toxic, nobody wants to be associated with it,” but on the other hand, not recognizing and recording failures tends to suppress experimentation. “If you don’t have any failures, that probably means you’re not trying enough things.”

One group had discussed innovation for social impact and the challenge of measuring it. An innovation architect for a software company said he was trying to implement “10 percent” projects in which employees would use 10% of their time to do something to help society or the environment. But needing to demonstrate a financial return posed difficulties. Another participant, a financial services executive, noted that in his industry there was a non-profit organization to help corporations determine if they’re improving their customers’ financial health. That was an example of a resource that could concretely measure social impact.

Singh noted the value of “cross-industry cross-fertilization” in looking across companies and sectors for inspiration and solutions, as the participants had done.

What Are the Top Most Effective Innovation Metrics? Lessons From Growth Leaders

How do growth-leading companies promote and measure innovation? asked Wharton marketing professor emeritus George Day. One way they don’t do it is through “innovation carnivals,” he said. “There’s lots of balloons and hoopla, and then everybody goes back to work and forgets that they’re supposed to ‘be lean’ or ‘find a blue ocean’ or build an innovation dashboard.” It’s a quick fix at best, not a long-term solution, he said.

Day presented research on companies that have fast organic growth driven by innovation. He discussed his study of 192 senior innovation executives in industries ranging from consumer goods to financial services to biotechnology. Day and colleagues identified four “innovation levers” that stood out when it came to the top 25% of companies in each sector. “These are what consistently separate growth leaders from everybody else.”

First and foremost, Day said, these companies invest in attracting and retaining innovation talent. If you’re an incredibly talented software developer excited about the latest AI developments, for instance, you’ll want to go to a place with a track record and an innovation infrastructure that’s willing to support you and let you take risks.

Day continued to the second most prominent innovation lever of successful companies: They encourage “prudent risk-taking” and they signal to the culture that they are tolerant of risk and failure. He gave the example of 3M, a company that dissects and extracts lessons from projects that don’t work out, because they have “discovered over the years that most of their really successful new products were the result of an earlier failure.”

The third most notable lesson from growth leaders was to adopt what Day called an “outside-in” approach. These companies have a wide-angle lens on what’s happening in the broader ecosystem with partners, competitors, and customers. They try to stand in customers’ shoes and think like them, and they exploit anomalies occurring in the marketplace. This is as opposed to “inside-out” thinking, which is starting with your current market position, resources, and capabilities and deciding how else you can apply them. (That’s useful too, said Day, but ultimately you need both.)

Finally, growth-leading firms align their metrics and incentives while avoiding measurement traps. Day discussed the seven most commonly-used metrics across all the companies in the study, which included the idea pipeline, the number of new products launched, revenue growth, customer satisfaction, return on investment in innovation, profit growth, and percentage of sales from new products. He asserted that all but the first two are overly outcomes-oriented and also can’t be reliably attributed solely to innovation. More focus should be placed on process effectiveness metrics, he said.

Overall, Day emphasized that the number one lesson from organic growth-leading firms was their focus on developing their organization’s innovation talent. He observed, “Peter Drucker had it right: you can only do as well as the people you have.”

Summing up the conference, Singh characterized innovation as “messy, complex, and uncertain” and said devising effective innovation metrics is not an easy task. But he noted that the growing presence of digital — having more data — offers an advantage in connecting the process of innovation to outcomes.

He also observed that time-to-market has “compressed a bit,” which can be a downside but also an advantage, in being able to demonstrate faster results from innovative projects.

Ultimately, Chaudhuri said, “you have to link everything to your competitive advantage, your strategic goals, and your organizational structure. There’s no one answer for everybody.” Participants left with new frameworks and practices to consider how their own organizations might more effectively promote and measure innovation in a challenging business environment.