By Wharton’s Rahul Kapoor, John Paul MacDuffie, and Daniel Wilde. This is an updated version of an analysis originally published in February 2017.

The Mack Institute’s Program on Vehicle and Mobility Innovation (PVMI) sponsored three technology forecasting challenges held between 2016 and 2020 focused on the question of when (and whether) automotive innovations such as electric vehicles will achieve mass market acceptance. These challenges included questions on consumer behavior, technological developments, and government policies that have the potential to propel the trend forward — or hold it back.

One key factor affecting consumer adoption of electric vehicles is the price and performance of batteries, so each of the three challenges included a question about the cost per kilowatt-hour (kWh). Read more about the original question here.

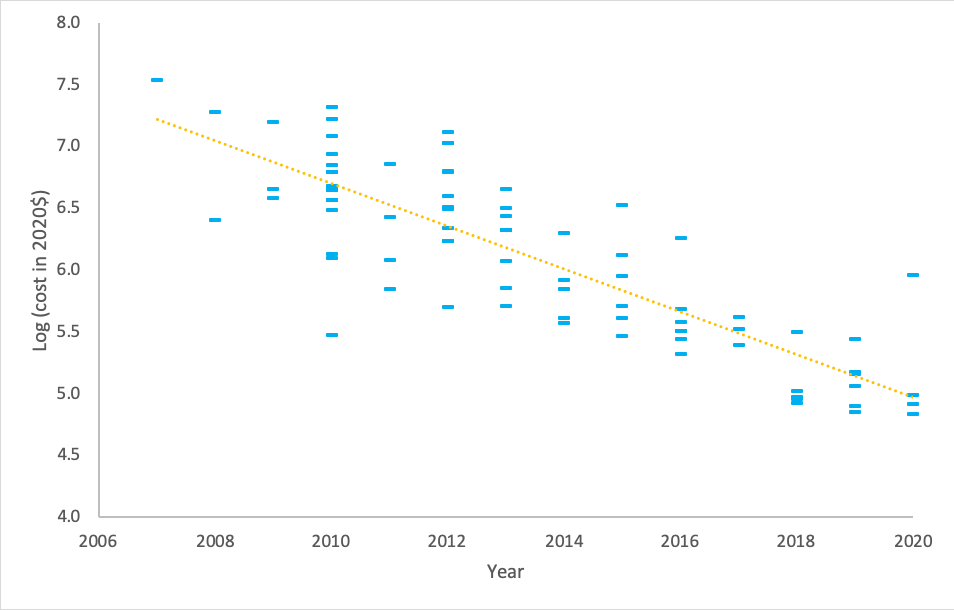

Here we describe the methodology and the results for the industry-wide average cost estimate of lithium-ion (Li-ion) battery packs in 2020, based on the same methodology as reported in a 2015 article in Nature Climate Change (Nykvist and Nilsson, 2015). Our analysis shows a 16% annual decline in the cost of battery packs between 2007 and 2020, and the industry-wide average cost of battery packs in 2020 was US $144 per kWh. Previously, we found the annual decline in the cost of battery packs between 2007 and 2019 to be 16% with industry-wide average cost of battery packs in 2019 to be US $161 per kWh.

Data Sources

Replicating the methodology in the Nature Climate Change article, we used “Electric vehicle Lithium Ion battery cost” as keywords to identify recent articles, news items, and expert and industry statements from Google’s search engine and reviewed the first 100 hits. We also used the same keywords in the Web of Science database and identified recent academic journals and publications and reviewed the first 100 hits.

Since the battery requirements for hybrid vehicles are different from those for electric vehicles, the data on costs of battery packs used only in hybrid vehicles was not included in the analysis. However, when information on battery packs for both types of vehicles were combined into one cost estimate, that estimate was included in the analysis.

This data was supplemented with additional cost estimates for individual car models such as Tesla Model S, Chevrolet Bolt Electric Vehicle, Nissan Leaf, BMW i3, Ford Focus Electric Vehicle, BYD Yuan, BAIC EU, Tesla Model 3, Renault ZOE, Baojun E100, and Audi e-Tron based on public statements made by the company. Furthermore, the battery pack replacement costs, found in articles and public company statements, were also included in the analysis.

Aggregation Method

The method yielded 54 new cost estimates. Cost estimates that duplicated data from another reference source were omitted from the analysis. Also, cost estimates for battery cells was not included as these costs are only a fraction of the costs for the battery packs. Finally, cost estimates prior to 2014 were also not included in the analysis to preserve the comparison with the Nature Climate Change article.

For references that provided a range of costs, the mean value of the highest and lowest values in the range was used. All costs in foreign currencies were converted into US$ based on historical exchange rate data from US Federal Reserve, and all costs were inflation adjusted to 2020 US$. The final dataset for the analysis comprised of 85 unique cost-estimates between 2007 and 2020 (53 estimates from the original article, 32 estimates for the years 2014-2020). The cost data was then log transformed and fitted using a simple regression equation of the trend line of the form shown in the figure below.

Take a closer look at the data used in this analysis (download).

Great Study, is there a specific publication citation?

Hi Mike,

Feel free to cite this as a blog post authored by Rahul Kapoor and John Paul MacDuffie according to whichever style guide you prefer.

Is it possible to obtain data from graph shown above in one excel table?

Hi Danijel, Did you get a chance to download the spreadsheet linked at the bottom of the post? It’s got several pages of data, including the battery cost data. Please let us know if you still need more information!

Something I”d really like to add to my post is that a dedicated high voltage battery system (Method 1) really is the best solution in terms of functionality. In my opinion, the way forward is to go with not a high voltage battery system, but a high voltage battery *standard*. That is, a battery physical format and set of minimum operating standards used by more than one company/brand. Much as is the case with computer operating systems, the only way a high voltage battery system can commercially survive is if it has a critical mass of applications. There are a lot of applications beyond the world of power tools and outdoor power equipment for which a 36v+ cell would work. Small vehicles, automotive starting systems, large drones, communication equipment, r/c hobby applications, portable appliances, audio equipment, medical devices, energy storage banks, etc. the list is endless. This is coming some day, because right now power tool manufacturers are in a race to the bottom on battery costs. When the previously ample margins on battery sales get thin enough, there will be a lot of pressure to leave the battery system to a dedicated battery company pushing a widely adopted standard format. This new era, will ironically enough, resemble the corded tool era, with tool manufacturers pushing the competence of their tools rather than the range of applications on a proprietary battery system.