The Mack Institute co-hosted its annual Wharton Technology and Innovation Conference on April 12 and 13, 2014. This guest post by Glenn Hoetker (W. P. Carey School of Business, Arizona State University) summarizes one of the papers for which he was a discussant.

In the global competition for innovative success, location matters.

The success of R&D-intensive firms depends on the domestic availability of high-quality resources. Institutions that support the creation of new knowledge are critical, as is the ability to capture value from that knowledge. Within a firm’s home country, variations in key factors will support or stymie innovative success. These factors include the education of the workforce, protection of intellectual property, access to funding, and so on.

In order to complement domestically available resources, firms often conduct R&D globally. Given the challenges of absorbing and leveraging knowledge from unfamiliar, distant settings, however, this strategy is no guarantee of success.

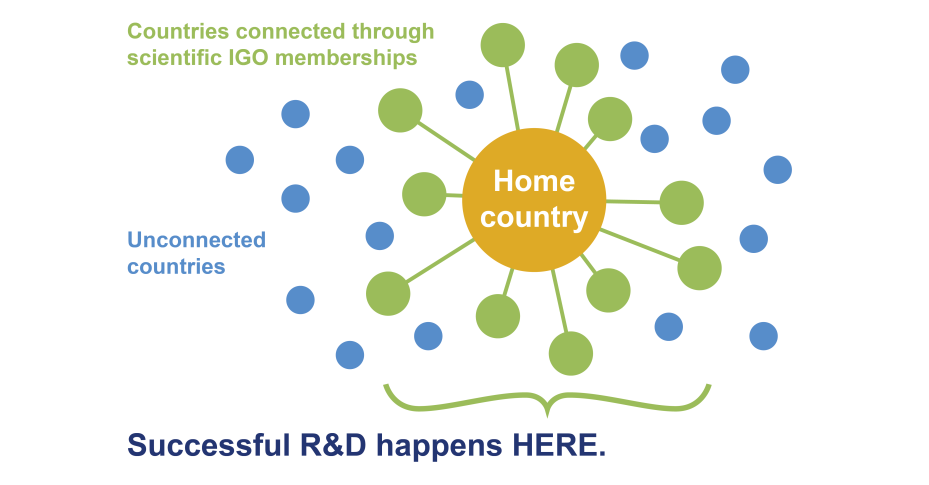

New research by Anupama Phene (George Washington University) and Srividya Jandhyala (ESSEC Business School, Singapore) suggests that a firm’s home country can impact the outcome of its global R&D efforts, not just its domestic R&D efforts. Here’s how: Countries engage in complex networks of scientific exchange through memberships in learning-oriented inter-governmental organizations (IGOs), such as the World Intellectual Property Organization and World Meteorological Organization. As these organizations empower interaction between scientific communities in different countries, interpersonal networks form and common practices are shared. Phene and Jandyala reasoned that these networks make it easier for firms to learn when conducting R&D in countries with which their home country had common memberships in scientific IGOs.

Their expectation was confirmed in a study of U.S. semiconductor firms from 2000 to 2005. The closer the alignment between the location of a firm’s R&D activities and the countries to which the U.S. was closely tied through membership in scientific IGOs, the more innovative the firm was. A firm’s R&D activities, it appears, are more effective when they take place on the foundation of scientific ties formed at the country level.

The take-aways? Managers deciding where to locate R&D activities often focus on what is distinct about each possible location. Phene and Jandyala’s results suggest that they should also consider what the locations have in common as a result of long-standing country-to-country scientific ties. Their research also suggests that policy makers should value membership in scientific IGOs—often viewed as primarily shaping public science—as a possible source of competitive advantage for their domestic companies.